A colorful genome: meet the rare Mediterranean White-spotted Yellow Wart Slug

- Jul 31, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 5, 2025

The White-spotted Yellow Wart Slug’s reference genome opens new doors to a better understanding of this unique Mediterranean species, its history, adaptations and factors threatening its survival.

The White-spotted Yellow Wart Slug (Phyllidia flava) is a one-of-a-kind bright orange sea slug species only found in the warm waters of the Mediterranean. Biodiversity Genomics Europe has generated the first reference genome for this species with the help of citizens and researchers. In this article, we hear from Carles Galià Camps, the researcher who proposed the sequencing of the species and took part in the sampling campaign to find the tiny ocean dweller. Carles shares his enthusiasm about the species (and nudibranchs in general), explains how a reference genome can be used to support conservation and tells us how this project benefitted from collaboration between scientists and citizens who share a passion for the sea and its life forms.

Watch the video for highlights of this conversation and read the full interview below:

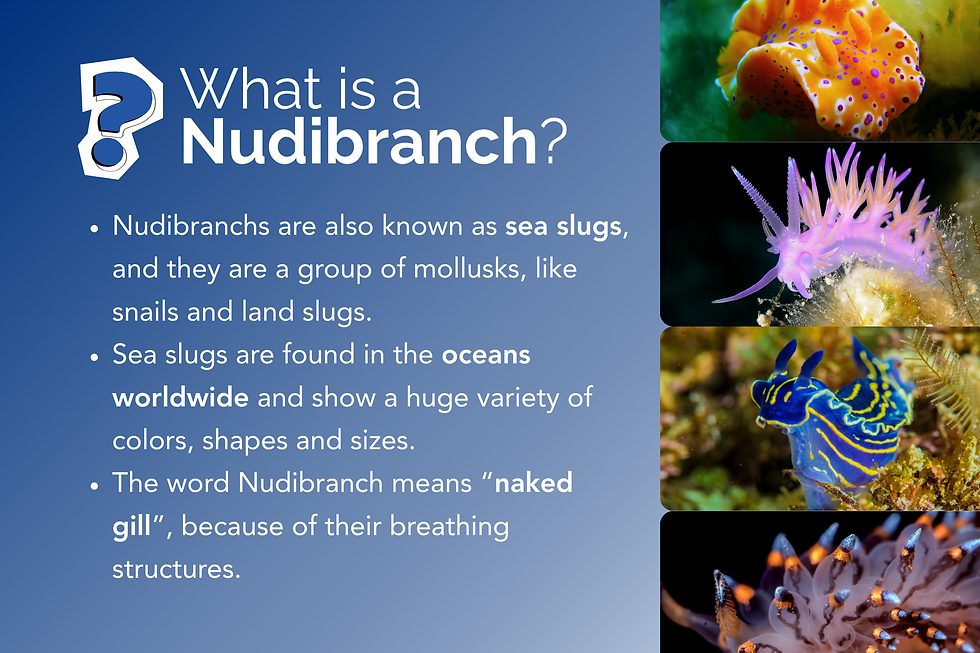

Carles Galià Camps is a Catalan young postdoctoral researcher at the Spanish National Museum of Natural History. He is a geneticist interested in knowing how species evolve and get adapted to new conditions. His heart was stolen by nudibranchs, also known as sea slugs, and since then he has been trying to generate new knowledge about them, specifically on their evolution and their phylogenetic relationships.

Could you introduce Phyllidia flava and highlight some interesting facts about this species?

Carles Galià Camps: To me, Phyllidia flava is one of the most unique nudibranchs (sea slugs) worldwide. This is because it has many unique characteristics. The first is that it is the only species of the genus in the Mediterranean Sea. All the other species of the same genus are found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. This is because when the Tethys Sea closed, there were two different Phyllidia communities, being Phyllidia flava the last Phyllidia species on the Mediterranean side of the Tethys Ocean, whereas the genus was very successful in the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. That's something really unique.

The other thing is that this sea slug species has a really close relationship with a sponge species, which it feeds on. Actually, this is not only a prey-predator relationship, but the sea slug is also capable of stealing some of the metabolites of the sponge. Because of this behavior, it is able to produce some metabolites which are deterrents and help the species disturb possible predators. Sometimes these sea slugs get stressed because they notice we are taking pictures of them and they start to secrete an orangish substance, which is this deterrent. That’s why you should never poke one of these! It’s really easy to see when you are annoying them and that they are defending themselves thanks to that sponge.

In general, nudibranchs usually breathe through the skin because they are so small that they don’t need lungs or any specialized organ. In some cases, if they are large enough, they have gills, which are usually found near the anus, in the animal’s back. But this is not the case for Phyllidia and other Phyllididae species because they have a unique structure, which is a gill in the lower-lateral side of the body. And no other sea slug family besides this one has it. So it’s another unique characteristic of this species.

Because of all of that, I think that Phyllidia flava is awesome, and it has lots of potential to teach us about evolution, sea biology, and many other topics.

Why is it so exciting to study nudibranchs?

Carles: Nudibranchs are absolutely wild. If you’re not familiar with them, they’re basically mollusks - like snails - that have lost their shells. Normally, a shell provides physical protection against predators, but nudibranchs had to evolve other strategies to survive. So, in a way, they were like, Oh no, I need to figure something out! They’ve developed an incredible range of defense mechanisms, most of them chemical, such as P. flava’s interaction with the sponge that I mentioned before. There are other nudibranchs that feed on anemones and corals. Instead of keeping the chemical metabolites, they actually store the nematocysts - the stinging cells from their prey - and can use them to sting predators. That’s insane!

And then there are the sacoglossans, also known as the “solar-powered sea slugs", which actually are not “nudibranchs”. They feed on algae and are able to store chloroplasts in their bodies, potentially allowing them to photosynthesize, at least to some extent. While this ability still needs full scientific validation, what we do know is that they can store these chloroplasts long-term and digest them when needed. This adaptation is crucial because algae often have seasonal growth cycles, so these sea slugs have found a way to maintain a backup food source when algae aren’t available.

Despite not being listed as endangered by the IUCN, Phyllidia flava is considered highly vulnerable. Can you explain the main threats to this species?

Carles: There are two main factors that can be seen as threats to this species: the fact that it is naturally rare, and human-made impacts: The first one is that the species is rare, so there are not that many animals. And the sponge that it feeds on is also rare, so there’s a convergence of rareness and difficulties in finding it. And then there are human-made effects. Among them there is ocean warming. We don’t really know yet how it will impact the species, but for sure, it will impact it, especially the population structure of the species. This sea slug is distributed across the whole Mediterranean, but some populations will disappear due to the warming, and some others may be enhanced. In any case, though, its genetic richness will drop, the population structure will change, and with this drop in genetic diversity, its resilience to climate change and changing environmental conditions will be diminished. So in the near future, I think that this will be the main issue that can threaten this species.

Another main human-made threat is trawling. This species lives on sponges but when there is trawling for fishing, they just take away lots of those sponges - and the regulation somehow doesn’t contemplate it. As I said, the sponges are the main habitat of Phyllidia, and well… It's a vicious cycle. If we keep taking the food out of the sea along with some Phyllidia, Phyllidia will suffer more to find food, and eventually, I think that Phyllidia flava will just disappear from the Mediterranean.

It’s a combination of all of these factors: the rareness of the sponge, the rareness of the nudibranch, climate change affecting populations and genetic diversity, and finally, human-made impacts that are eroding the original environmental conditions.

How will the new reference genome help science address these threats?

Carles: I really love population genomics. As a scientist, that was the topic of my PhD thesis and what I’m working on. What we’ve seen is that if you have a reference genome, your results improve significantly, and you can infer any pattern - any evolutionary pattern, any adaptation pattern… basically anything you may want. Once there the reference genome is available, we can gather samples from the species across its distribution, across the whole Mediterranean, and try to understand the genetic richness of the species and the mechanisms it has to overcome unusual environmental conditions, such as marine heatwaves and salinity shifts.

Then, there are many other issues that can be tackled with the help of the reference genome. Remember that this is the last remaining species of the genus Phyllidia in the Mediterranean - a true relic - because it split from all the others many years ago.

This makes it an important calibration point in phylogenetic analysis. In other words, you can determine when Phyllidia flava diverged from the other Phyllidia species, estimating that this split happened X years ago when the Tethys Sea closed. With this reference point, researchers can tackle broader questions related to evolutionary timelines and demographic changes.

Another fascinating aspect that can be explored with its genome is how Phyllidia flava absorbs deterrent molecules from its sponge prey and modifies them for its own defense. To me, that’s mind-blowing - this species not only uses its food source for nutrition but also repurposes it for self-defense. This is something that many nudibranchs do, but Phyllidia flava stands out as a perfect model for studying this unique adaptation.

It must have been difficult to sample such a tiny animal that lives deep underwater. Can you share the story of how the sampling happened and the role of citizen scientists in this?

Carles: When I first learned about ERGA-BGE's call for proposing species to have their genomes sequenced, I knew I wanted to participate. I study various animals, but my heart belongs to nudibranchs, and I wanted to sequence a nudibranch because there are not many reference genomes available for this group. I think this is one of the few, if not the first, chromosome-level assembled nudibranch genomes, which is top-tier.

However, I don’t scuba dive that much. My main research duties involve writing and analyzing data, and while I love that kind of work (field work), I don’t always have time to be in the ocean. When it’s time to go to the sea, I often can’t make it. I knew about Miquel Pontes - he is passionate about the ocean and has many initiatives related to nudibranchs. Right now, he’s moving into new fields, working with corals, collaborating with many people, and developing a network of ocean enthusiasts.

Miquel even created a WhatsApp group where every week, he announces, “I’m going scuba diving. Who’s coming?”. He organizes trips, makes checklists of nudibranch species in different areas, and even explores pools in Barcelona to document biodiversity. Even though he’s not a scientist by training, he knows an incredible amount about marine life. Most importantly, he knows where to find the species. As a researcher, I only have the theory, but he goes to the sea every week and has seen Phyllidia flava over and over again. He knows exactly where to look, which sponges to check, and how to spot them. For me, talking to him was essential. I had the idea and could go to the ocean, but my chances of finding Phyllidia flava on my own were much lower than if I worked with him.

For the sampling campaign, it wasn’t just the two of us. We were looking for a tiny sea

slug (about two centimeters) blending perfectly with orange sponges, making it really difficult to spot. So we used the WhatsApp group and invited people to join. They came, and we gave a short briefing. We explained what we were doing, why we were collecting Phyllidia flava, and the importance of sequencing its genome. They were super engaged and excited to be part of the project. Then, we jumped into the sea and started searching. In the first dive, we had four people. The second time, six. Both were unsuccessful. It wasn’t until the third attempt, with four people again, that we finally found it - It was a real mission! These dives were on different days in different locations. You never really know where to find these animals. On land, you can scout the area in advance, but underwater, it’s much harder. Unless you’ve been to the same place dozens of times, you’re relying on luck. That’s the challenge, but it also makes each discovery even more rewarding.

But in the third attempt we finally found Phyllidia flava! It was Miquel who spotted it, actually. His experience and sharp eye were key in locating it. Afterward, we celebrated. We went to a bar, had a beer, and talked even more about the species. It was a great moment. This experience showed me how important it is to have people like Miquel. He engages with others, bringing citizens together week after week. He shares his passion, but he also connects with scientists, combining our strengths to reach common goals. It’s important to gather people like him, because they can really help researchers, they enjoy what they do, and they spread awareness. In the future, the people involved in the sampling of the species will care about it and share their experiences with family and friends. It’s a great way to spread knowledge and raise awareness about marine life.

Learn more:

Interview and editing by Luísa Marins